Disability studies views disability in general as a social construct. Rather than one universal experience of disability, this view acknowledges that disabled people have different experiences across time and cultures, and ideas about what disability means and who is disabled are defined by humans. Disability studies also recognizes a difference between impairment, or body-mind difference, and disability.

The same concepts apply when we talk about developmental disability. People can have impairments in their bodies and brains. For instance, a person may communicate nonverbally. A person may have seizures. A person may process the world in a way that makes reading harder. Calling developmental disability “social constructed” does not mean that all of our bodies are the same. It is does not mean that all of our minds are the same. We should not ignore differences. We can still talk about how impairments can be difficult for people to experience. However, it is our society that makes meaning from difference. Our society values or devalues differences. Our society creates diagnoses like autism, epilepsy, and dyslexia. By requiring reading, prioritizing talking over other communication, or allowing strobe lights and other seizure triggers, society disables people with specific impairments.

Who is viewed as having a disability, and how does this shift throughout time? Thomas Armstrong argues that developmental disabilities, learning disabilities, and mental health disabilities are defined by the societies and eras in which we live. He writes, “No brain exists in a social vacuum. Each brain functions in a specific cultural setting and at a particular historical period that defines its level of competence” (2010, p. 15). People with the same brain differences are regarded completely differently dependent on the social context. The places and times we live in make things easier or harder for people with developmental disabilities. Armstrong posits that “being at the right place at the right time seems to be critical in terms of defining whether you’ll be regarded as gifted or disabled” (p. 15).

People with developmental disability were treated differently according to time, culture, and understanding of disability. Here, a man with epilepsy is blessed by Saint Valentine.

Saint Valentine blessing an epileptic. Colored etching. Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Disability historian Kim Nielsen (2012) notes that the concept of disability changed throughout American history. The idea of what “disability” meant was not the same. Before Europeans colonized North America, some indigenous people viewed individuals with disabilities differently than we do today: “A young man with a cognitive impairment might be an excellent water carrier. That was his gift. If the community required water, and if he provided it well, he lived as a valued community member with no stigma” (2012, p. 3). People with what we now call “developmental disabilities” were included in the community. Often, they were not viewed negatively. Nielsen explains, “Most indigenous communities did not link deafness, or what we now consider cognitive disabilities, or the shaking bodies of cerebral palsy, with stigma or incompetency” (2012, p. 4). Once European settlers began colonizing North America, they brought disease and violence. War and illness shifted resources among groups and changed group values. These changes impacted disabled people. The same people who were included in their communities might not have a place anymore. Nielsen explains that suddenly, for people with impairments including what we now call developmental disability, “Though they may have possessed excellent storytelling or basket-making skills, wisdom, the ability to nurture children, these things meant little in the face of overwhelming communal stress” (2012, p. 18). In other words, colonialism brought disease and war. New and dangerous conditions made disabled people less valuable to the group, less likely to be a part of the group, and more likely to die.

European colonists brought different views of people with developmental disability. Kim Nielson explains that in the 1600s, people with some physical impairments could be accepted because they participated in work. At the same time, “those that today we would categorize as having psychological and cognitive disabilities attracted substantial policy and legislative attention by Europeans attempting to establish social order, capitalist trade networks, and government in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century North America” (Nielson, 2012, p. 20). Europeans made laws and policies that impacted disabled people’s lives. In Colonial America, some people with developmental disability and psychiatric disability were sent to institutions like almshouses and asylums, while others lived in the community or were locked away at home. Nielson explains, “The decades surrounding the American Revolution were a period of transition for those with mental and cognitive disabilities, in which some were referred to experts outside the family and some were not” (p.38). Nielson sees this as a shift toward the medical model of disability, in which disability is seen as an individual problem that requires medical intervention. People started turning to doctors to help them understand their family members’ disabilities.

Disabled people were not the only ones impacted by negative ideas about disability. People of color, women, immigrants, and people now considered LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and asexual) were impacted by ableism and the medical model of disability. The concept of feeble-mindedness was misused to control and oppress marginalized people like woman and people of color. Ableism is structural discrimination against disabled people. Ableism shares roots with other oppressions, like racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and xenophobia. Nielson notes, “The racist ideology of slavery held that Africans brought to North America were by definition disabled. Slaveholders and apologists for slavery used Africans’ supposed inherent mental and physical inferiority, their supposed abnormal and abhorrent bodies, to legitimize slavery” (p. 42). Slavery was inhumane and operated through racism. Slavery also relied on negative ideas about disability. As medicine took hold in the 1800s, “medical expertise regarding women’s biological deficiencies buttressed the exclusion of white women from higher education, voting, and property ownership” (Nielson, 2012, p. 66). So medical model disability language was used to deny women’s rights. People today considered LGBTQIA were “diagnosed as sexual perverts” and were deported, sterilized, and institutionalized (Nielson, 2012, p. 115). Indigenous people were mistreated, killed, and barred from citizenship, while potential immigrants were scrutinized for signs of disability. During the time between the American Revolution and the Civil War, “Disability, as a concept, was used to justify legally established inequalities” (Nielson, 2012, p. 50).

Samuel Gridley Howe believed people with developmental disability could learn and work, and helped establish schools, including those that served students with developmental disability (Nielson, 2012, pp. 67-68). Asylums were segregated racially. Institutionalized people of color and indigenous people received worse treatment (Nielson, 2012, p. 92). Institutions exposed disabled people to extreme abuse and neglect. People with developmental disability were among the most targeted for institutionalization.

The late 1800s to the early 1900s was when institutions really became central to the plight of people with developmental disability. Starting in the mid-1800s, children and adults with developmental disability were sent to “training schools,” “colonies,” and “institutions for the feeble-minded” (Jirik, 2014). There were smaller private institutions, as well as an influx of large public institutions. Katrina Jirik (2014) explains that “As the laws changed, allowing lifetime commitment to the institutions,” they went from educating people who weren’t allowed in public schools due to disability to calling it “vocational training” to use inmates for “the labor needed to run the institution” (2014). Institutions became places where people were warehoused for their whole lives. People with developmental disability faced neglect, abuse, medical experimentation, and death in institutions across America.

Historical Perspectives on Developmental Disability

As eugenics became popular, institutions became places to separate and sterilize Americans with developmental disability and other disabilities (Jirik, 2014). Eugenics is the idea that some people are smarter, healthier, and better because of their genes. In 1883, Sir Francis Galton came up with the term “eugenics,” meaning “well-born” (Kurbegovic & Dyrbye, n.d.). He believed that by encouraging certain people to marry and have children while discouraging or stopping other people from doing so, humans would improve and get rid of problems. Galton, who was cousins with Charles Darwin, is known as the father of eugenics. As Lennard Davis (2013) writes:

On the one hand Sir Francis Galton was cousin to Charles Darwin, whose notion of the evolutionary advantage of the fittest lays the foundation for eugenics and also for the idea of a perfectible body undergoing progressive improvement. As one scholar has put it, “Eugenics was in reality applied biology based on the central biological theory of the day, namely the Darwinian theory of evolution” (Farrell 1985, 55). Darwin’s ideas service to place disabled people along the wayside as evolutionary defectives to be surpassed by natural selection. So eugenics became obsessed with the elimination of “defectives,” a category which included the “feebleminded,” the deaf, the blind, the physically defective, and so on. (Davis, 2013, p. 3).

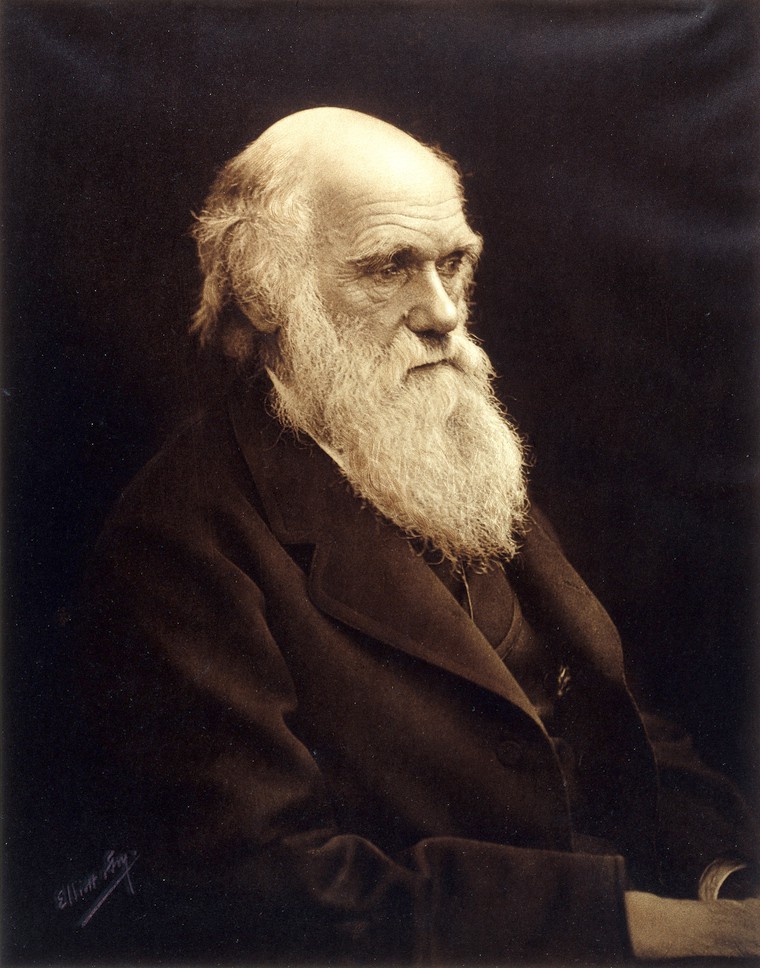

Charles Darwin was a scientist and explorer. In 1859, his theory of evolution, based on his observation of animals, was published. The title of his book was On the Origin of Species. One part of Charles Darwin’s theory was natural selection. In 1859, Darwin wrote, “It may be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good” (1859/2009, p. 83). Natural selection meant that the animals (including ancestors of humans) who adapted best to their environment and had the best qualities would be most likely to survive, mate, and have offspring. The genes of the “fit” animals would also live on in the successful animals’ descendants. On the other hand, natural selection also meant that the least fit animals, who did not adapt “well,” would be unlikely to be chosen as a partner, and therefore pass their genes down to future generations. One biologist, Herbert Spencer, framed natural selection as the idea of “survival of the fittest” (Kurbegovic, 2014).

Charles Darwin.

Portrait photograph of Charles Darwin. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain

People got excited by Charles Darwin’s theories. Some people began to think that natural selection should apply to human beings in society. Erna Kurbegovic (2014) says,

Social Darwinists tried to explain inequality between individuals and groups by misapplying Darwinian principles. Thus, those who were successful were seen as superior to those who were not. This type of thinking helped set the stage for the eugenics movement to emerge. (Kurbegovic, 2014).

Social Darwinists used Darwin’s theories to try to understand society and thought that groups of people who were struggling were biologically worse.

Natalie Ball (2013) describes how Charles Darwin contributed to eugenics. Ball explains that Darwin’s theories advanced biology and genetics research, so people used his theories to justify eugenics. She writes,

The segregation, sterilization, and murder of various groups was justified by some as being done for the greater good of evolution – those groups were considered to be ‘less fit’, and by preventing their reproduction, advocates argued that the human race would improve and evolve into a better species. (Ball, 2013).

Darwin’s part in the eugenics movement is shown by his family members, including his cousin Sir Francis Galton, the father of eugenics, and two of his sons, who were involved in eugenics leadership and promotion (Ball, 2013).

Was Charles Darwin himself a eugenicist? Eugenicists are people who studied, practiced, and believed in eugenics. In his book The Descent of Man, he included racist arguments that fit into eugenicist thought, while arguing against laws controlling who had babies (Ball, 2013). But as Natalie Ball (2013) writes, “Whether or not he would have agreed with it, the theory of evolution and natural selection provided a scientific and theoretical basis for eugenic ideas and actions” (Ball, 2013). Arguing about whether Charles Darwin was or was not a eugenicist is not important. What’s important is how his ideas supported eugenics as a legitimate science.

Eugenics is part of the history of people with developmental disability. Eugenicists wanted “better” people to have children and live freely. Eugenicists thought some people weren’t worthy of having children, living in the community, or even being alive. In America, people thought of eugenics as a “science.” Many Americans supported public policies based on eugenics. At Ellis Island, disabled immigrants, including immigrants with developmental disability, were judged and deported (Nielson, 2012, p. 103). States passed laws to sterilize disabled people. American eugenicist Harry Laughlin’s “model sterilization law became internationally renowned, eventually taken up by Adolf Hitler in his own bid for a national racial purity” (Nielson, 2012, p. 102). In 1927, the United States Supreme Court said it was acceptable to sterilize people with developmental disability. It didn’t matter if people wanted to have children. The Buck v. Bell case said doctors could sterilize disabled people without their permission. The Supreme Court said it was best for public health to stop people with developmental disability from having children. They believed that parents passed developmental disability to their children (Buck v. Bell, 1927).

American eugenics made a worldwide impact. As Nancy E. Hansen, Heidi L. Janz, and Dick J. Sobsey write (2008), Nazis put laws in place with “similar, if more radical, eugenic understandings [which] resulted in the systematic murder of almost 250,000 disabled people during the period of National Socialism in Germany” (pp. S104-S105). Some Nazi policies were based on American and European laws. Other Nazi laws went further by killing people they saw as unworthy. One group Nazis targeted were people with disabilities.

A 1933 Nazi propaganda poster tells Germans to talk to their doctors about genetic disabilities.

People should be open and candid with their doctors about hereditary illnesses, so that the German state can act to eliminate them. Color lithograph, 1933/1945. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Eugenics and Nazism play a role in autism history. Historians credit both Dr. Hans Asperger and Dr. Leo Kanner with creating the autism diagnosis (Czech, 2018, p. 4). The two doctors each had “types” of autism named after them—Kanner’s autism and Asperger syndrome (Silberman, 2015). Today, different autistic people with different support needs share the same disability name. During the Nazi regime, Asperger was a doctor in Austria. Some of Asperger’s ideas about autism changed our understanding of developmental disability. People in English-speaking Western countries often thought Asperger resisted the Nazis and protected disabled people (Czech, 2018, p. 3). Newly-available documents from Nazi times show that the real story is more complicated. According to Herwig Czech (2018), Asperger referred at least two children with developmental disability to Am Spiegelgrund. Am Spiegelgrund was an institution that Nazis used to murder disabled people (p. 20). When Nazis sterilized disabled people, Asperger seemed ambivalent. New facts make older stories about Asperger harder to believe. Czech suggests to think about Asperger’s discoveries about autism in context (p. 32). In other words, remember that Asperger contributed to present thinking about developmental disability, but don’t forget his actions in Nazi-occupied Austria. As Czech points out, the roots of the autism diagnosis comes from a time of eugenics.

IQ as Eugenics

Eugenicists considered people with developmental disability genetically inferior. People with intellectual disability were seen as a threat. The invention of intelligence quotient (IQ) testing helped eugenicists to segregate people with intellectual disability. Thomas Armstrong (2010) explains how IQ testing came about:

In 1905 psychologist Alfred Binet was asked by the Paris public school system to devise a test that would help predict which students would be in need of special education services. He developed the original test, upon which IQ scores would be based, but his belief was that students could improve their performance on the test through further development and learning. It was a German psychologist, William Stern, who actually gave the test a ‘score’ that became the intelligence quotient of an individual. The most significant changes in IQ testing, however, took place when American psychologist Henry Goddard brought Binet’s test and Stern’s score to the United States. In contrast to Alfred Binet, Goddard believed that the IQ test represented a single innate entity that could not be changed through training. (pp. 141-142)

Eugenicists thought that intelligence was genetic, unchangeable, related to social and financial success, and necessary for moral citizenship (Roige, 2014). IQ tests were used to label people as “feeble-minded,” which put them at risk of being institutionalized and sterilized (Roige, 2014). According to Kim Nielson (2012), “Many in power… used Gregor Mendel’s scientific work on plant genetics and the newly developed Binet-Simon intelligence test to argue that criminality, feeble-mindedness, sexual perversions, and immorality, as well as leadership, responsibility, and proper expressions of gender, were hereditary traits” (Nielson, 2012, p. 101). By saying that morality and intelligence were passed down through families, scientists argued for laws that restricted people who fell outside of the norm. IQ scores were treated as evidence for the kind of lives people were allowed to lead.

Modern-Day Eugenics

Eugenics might seem like it should be a concept from the past, but unfortunately, it continues in present-day disability policy. Despite their eugenicist history, IQ tests still are used to decide disability diagnosis, schooling, and employment, as well as “ in courts…if the person is capable of informed consent or of parenting” (Roige, 2014). In other words, IQ scores or a diagnosis of intellectual disability can be used to restrict rights. Nancy E. Hansen, Heidi L. Janz, and Dick J. Sobsey (2008) state, “There are disturbing similarities between Nazi arguments concerning ‘quality of life’, ‘useless eaters’, or ‘lives less worthy’ and discussions of disability currently taking place among ‘mainstream’ geneticists and bioethicists advocating a value scale of humanness” (p. S105). Bioethics relates to the study moral questions about life and living beings. One famous philosopher, Peter Singer, has debated whether a baby with a disability who needs expensive healthcare has a right to life. Hentoff (1999) quotes Singer as writing that “It does not seem wise to add to the burden on limited resources by increasing the number of severely disabled children” in Should the Baby Live? and in Practical Ethics, “that the parents, together with their physicians, have the right to decide whether ‘the infant’s life will be so miserable or so devoid of minimal satisfaction that it would be inhumane or futile to prolong life’” (Hentoff, 1999). Reading Singer’s work can be jarring and upsetting from a disability studies lens. Singer’s arguments show that eugenics is still discussed and debated. This is part of what Hansen, Janz, and Sobsey are talking about when they write that there are “disturbing similarities” between eugenic arguments of Nazis and modern bioethicists (2008, p. S105). The authors also mean that some people who study and give medical advice about genes use language of eugenics when referring to people with genetically-linked disabilities. There have been many advances in genetics in the twenty-first century, from the Human Genome Project sequencing DNA in 2003 to present-day commercially-available genetic testing kits (Roberts & Middleton, 2017). When parents-to-be go to the doctor, they can find out whether their future children are likely to have an impairment linked to their genes. For instance, a doctor can tell somebody whether their child is likely to have developmental disability like Fragile X syndrome or chronic illnesses like cystic fibrosis. A genetic counselor is a professional who understands genetic conditions, discusses test results, and advises patients of options for treatment and reproduction. A genetic counselor might give advice to somebody who finds out through screening during pregnancy that the embryo has an impairment such as Down syndrome, spina bifida, hydrocephalus, or a heart condition. In this scenario, the genetic counselor would advise their patient about options to continue with or terminate the pregnancy.

One area of ethical concern is prenatal screening. During pregnancy, future parents can find out whether their child will have certain impairments. Doctors can diagnose some impairments that are linked to genetic or physical differences in fetuses. Down syndrome is one example of a developmental disability that can be diagnosed prenatally. A consequence of prenatal diagnosis in an ableist world is reducing the populations of people with certain impairments. A person can end a pregnancy if they find out the embryo has an impairment. For instance, “Since prenatal screening tests were introduced in Iceland in the early 2000s, the vast majority of women—close to 100 percent—who received a positive test for Down syndrome terminated their pregnancy” (Quinones, 2017). Julian Quinones explained that about eighty percent of expecting parents got the screening test, which involves “an ultrasound, blood test and the mother’s age” to estimate risk factors of genetic disabilities (Quinones, 2017). Compared to other countries, very few people with Down syndrome are born in Iceland each year.

Scientists are working hard to research genes and physical signs of more impairments. One developmental disability that scientists want to understand better is autism. There are large-scale research studies about autism and genetics. One giant research study is SPARK for Autism, which is aiming for thousands of genetic samples from autistic people and their families around the United States. SPARK says its purpose is “to help scientists find and better understand the potential causes of autism. … What we collect and learn will be shared with many autism researchers to help speed up the progress of autism research” (Simons Powering Autism Research, 2019a, para. 1). But when it comes to genetics and disability, disability rights groups question what will be done with the new information scientists find.

Currently medical professionals diagnose autism based on people’s behavior and developmental history. But what would it mean if autism could be tested for genetically, like with Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, and other impairments? Pat Walsh, Mayada Elsabbagh, Patrick Bolton and Ilina Singh (2011) write about how researchers are looking for a biomarker for autism—a measurable, predictable biological indicator of a specific condition that can identify “at risk” people, diagnose a condition, and/or provide “personalized treatments” (p. 605). Despite their scientific interest, Walsh et al. know that there could be ethical problems with finding a biomarker for autism. Autism is different for everyone, and people’s experiences with being autistic change over time. Walsh et al. (2011) said that “it is important that biomarker discovery in autism does not result in children being given a biological label that fixes and defines their potential and treatments” (p. 606). They are saying that it would not be ethical to use genetic testing to label a child with a type of autism. Then the child could become limited by what the test said. Another ethical issue is whether to view autism as a difference or a disability. Walsh et al. discussed how some disability rights and neurodiversity advocates have argued for viewing autism as a difference, not a disability. If finding a biomarker could lead to “prevention” of autism, then no matter what exactly is meant by prevention, it “assumes that autism is problematic” (Walsh et al, 2011, p. 608). One form of prevention would be prenatal genetic testing. At the time that the authors wrote the article, they thought it would be “unlikely” for one test to tell an expectant parent if their fetus is autistic and more likely that testing could identify different types of autism for parents-to-be and parents of babies (Walsh et al., 2011, pp. 608-609). The authors admit that making prenatal genetic testing available for autism could “could lead to embryo selection and elective termination (to avoid having a child with autism) becoming the norm” (Walsh et al., 2011, pp. 608-609). In other words, people may choose to terminate their pregnancy because of a chance that the fetus could be autistic, or choose to be implanted with what scientists say is a nonautistic fetus. In fact, the authors explained that there already are prenatal genetic tests for autism available in labs. However, the test looks for genetic variations “that are associated with autism” but should not be connected to autism without more research (Walsh et al., 2011, p. 609). Because the authors were interested in ethics as well as science, they recommended that autistic people and their families be involved in whatever clinical tests may emerge.

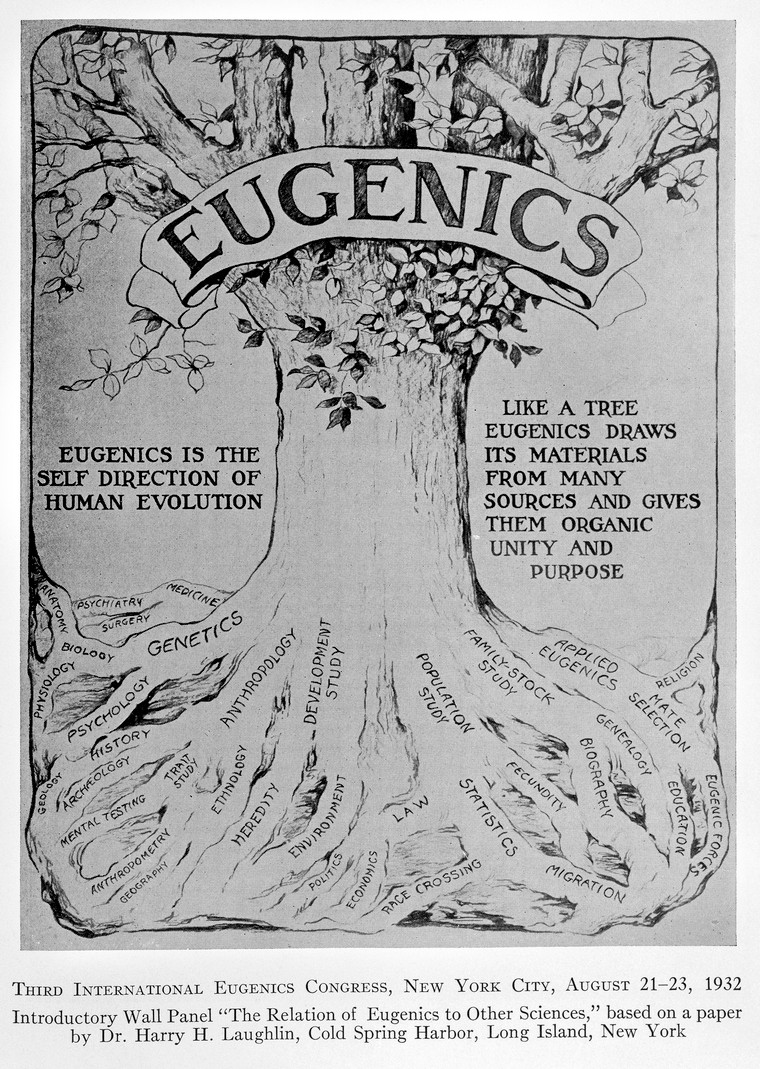

This wall panel was based on a paper by eugenicist Harry Laughlin and was presented in 1932 at an international eugenics conference at the American Museum of Natural History.

A decade of progress in Eugenics. Scientific. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Erik Parens and Adrienne Asch (2003) wrote a disability rights perspective on prenatal testing. Within their working group, they found that both people with disabilities and parents of children with disabilities disagreed about the purpose and use of prenatal genetic testing:

Although many members of Little People of America would not use prenatal testing to select against a fetus that would be heterozygous for achondroplasia (and who could become a long-lived person with achondroplasia), they might use the test to avoid bearing a child who would be homozygous, because that is a uniformly fatal condition. As participants at the 1997 meeting of the Society for Disability Studies suggested, some people with disabilities would use prenatal testing to selectively abort a fetus with the trait they themselves carry; and some people who would not abort a fetus carrying their own disability might abort a fetus if it carried a trait incompatible with their own understanding of a life they want for themselves and their child. A similar diversity of views toward prenatal testing and abortion can be found among parents raising a child with a disability. (Parens & Asch, 2003, p. 41)

Knowing somebody’s relationship to disability will not tell you how they feel about genetic testing. However, Parens and Asch wrote about shared concerns that disability rights activists have about prenatal tests: “it is the reality of using prenatal testing and selective abortion to avoid bringing to term fetuses that carry disabling traits” (Parens & Asch, 2003, p. 41). They recommend that geneticists and medical providers involved in pregnancy care learn about disability and “identify and overcome biases against people with disabilities” so they can share realistic information with patients (Parens & Asch, 2003, p. 45). So, their disability rights perspective on prenatal testing is that healthcare providers and potential parents deserve accurate information about life with disability and the purpose of testing, as well as the opportunity to consider their values about children and disability before they are confronted with medical decisions. Kruti Acharya (2011) highlighted advances in providing the sort of information for which Parens and Asch were advocating. A 2008 law, the Kennedy-Brownback Pre- and Postnatally Diagnosed Conditions Awareness Act, meant that when doctors tell families about Down syndrome or another impairment, they must give “accurate information” about the impairment and related disability resources (Acharya, 2011, p. 5).

People can submit a sample of saliva or blood and find out whether they have a gene or a change in their genes that is linked to an impairment. Everyone has genetic variations—differences from and changes to what is expected in DNA, which is like our genetic coding. But, certain genetic variations are linked to impairments. While Hansen, Janz, and Sobsey clarify that they believe modern genetic counseling is “not truly eugenic in its intent” (2008, p. S106), they warn that it also does not center disability rights. Even if it is not intended to be eugenics, though, does that necessarily mean that the impact is not eugenics? Hansen, Janz, and Sobsey also state that genetic counseling does not question Darwin’s principles that contributed to eugenics.

Eugenics can involve deciding who deserves to be alive. Eugenics can also involve deciding who is allowed to have babies. Even in 2018, Washington State came under fire for deliberating over a law change that would potentially make it easier for people with disabilities under guardianship to be sterilized against their own will. Autistic advocate and founder of the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN), Ari Ne’eman, wrote that Washington State “prohibits guardians from authorizing sterilization without court approval — but the state judicial system is currently considering a proposal […which] advocates with disabilities and the ACLU believe…will streamline the process and increase the number of guardians requesting the sterilization of those under their power” (Ne’eman, 2018).

The right to reproduce is not the only right in jeopardy for people with developmental disability. Although voting rights are supposedly protected under the Voting Rights Act (1964), the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act (1984), and the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990), the reality is that people with developmental disability have been prevented from participating in this part of citizenship throughout time. Disability historian Kim E. Nielsen (2012) explains that as far back as in Massachusetts colony of 1641, some people were exempt from public service and criminal punishment and protected from financial decision-making (p. 21). The list included women, children, older adults, and disabled people, illustrating how concepts around cognitive disability have often included groups viewed as different due to race, gender, age, nationality, or sexual orientation and marginalized by systemic oppression. Nielsen (2012) explains, “Between the 1820s and the Civil War, states also began to disenfranchise disabled residents by means of disability-based voting exclusions.…Virginia excluded ‘any person of unsound mind’ from voting in 1830 (it went without saying that women and African Americans were excluded from the vote)” (p. 76). These voting restrictions not only focused on perceived cognitive impairment, but also made a lasting impact to the present day. Switzer reported on a 1997 research study showing that forty-four states had laws that specifically prevented some people with disabilities from voting: “Some states refused to allow whole classes of people to vote (those variously termed idiots, insane, lunatics, mentally incompetent, mentally incapacitated, unsound minds, not quiet and peacable, and under guardianship and/or conservatorship)” (2003, pp. 181-182). Jaqueline Vaughn Switzer (2003) explains that voting is still not a national right for all people with disabilities.

Individuals with developmental disability are prime targets of modern eugenics. While the times and the specifics shifted, the denial of human rights continues for people with developmental disability. However, the history and present of developmental disability is not a straightforward story of victimhood. People with developmental disability resist ableism and advocate for rights. Resistance and self-advocacy offers a path forward for disabled people.